In the baby trenches

- melissa39316

- Nov 30, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 1, 2023

Feb. 12, 2016

I have just come back from a couple of weeks spent in St. Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, helping my daughter and daughter-in-law transition into motherhood. One forgets what a travail those first few weeks/months of parenthood can be: REM-deprived parents, bleary-eyed and more than slightly unhinged, stumbling like sleepwalkers into traffic, hit first by one transport truck, then another as they stagger across the multiple lanes that stretch between feedings; secretions, everything that can leak leaking . . . and a few you had no idea were capable of it; the mounting, terrible realization that your house, in and out of which you are accustomed to blithely pass, is closing in around you, entombing you. That sound like a vacuum suck? The tomb sealing shut.

Couple that with night and day turned inside out; the considerable pathos exhibited by the family dog, demoted from First Place, stricken, uncertain now as to his rank within the pack; the sluggish, incessant churn of the breast pump, punctuated by the string of commercials held together with gobbets of news that is CNN in the days leading up to the Iowa Caucus: ads for Trivago and Friskies and obscure medications trailing lengthy laundry lists of possible side effects, “up to and including death.” “You will be able to dance/leave the house without fear of soiling yourself/make love,” they promise, “Although there is the odd chance that you may also have a seizure/stroke/ or die.”

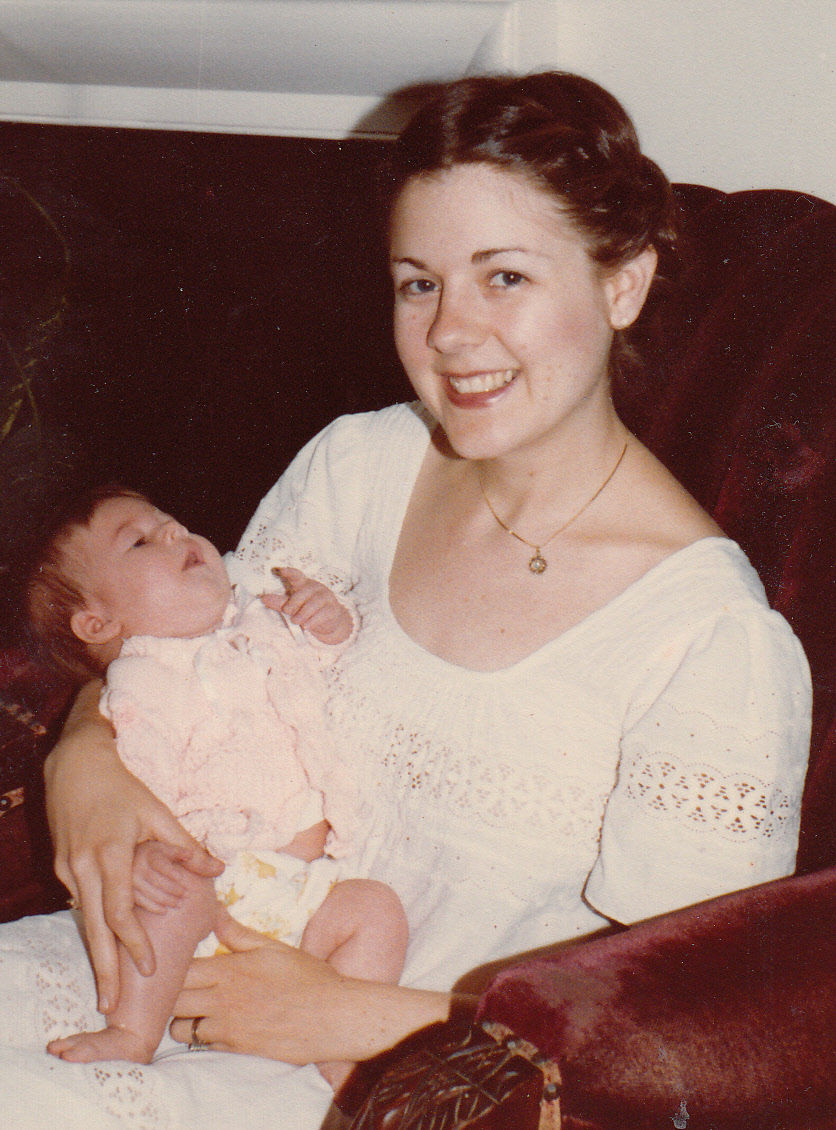

And at the center of this howling vortex, the bright new light of a glowing baby, in this case, my granddaughter, Victoria.

For prospective mothers childbirth looms large. It’s the great unknown, the question mark. Will it be painful? How long will it last? What if I have to have a C-section? Will the baby be OK?

What they don’t tell you . . . what we don’t tell you . . . is this: , if labour is like charging up a hill in full battle armour under a barrage of enemy fire, the first two months following the birth of your child are like finding yourself trapped within the trenches, thigh deep in foul-smelling mud, exhausted, shell shocked and despairing of any light whatsoever at the end of the tunnel. We don’t tell you this, because you have enough to worry about. We don’t tell you this because, unless reminded, as I was this past several months, we have forgotten what it was like. Indeed, the only memories I have from the period after Sabrina’s birth was waking up in the middle of the day to a plumber taking out the wall in our bathroom with a sledgehammer – apparently, pursuant to a neighbor’s complaint of a leak, he had rung our bell shortly after I put the baby and myself down for a desperately needed nap, and, upon not receiving a reply, entered the apartment and set about ripping out the wall. I erupted from the bedroom guns like a napalmed-she-cat. Hell hath no fury like the mother of a newborn awakened from a nap.

The other memory I have is of sitting on the couch for the 2 am feeding, leaden with fatigue, watching a PSA on heavy rotation that time of the night: at the end a long hall a closed door looms. From beyond the door comes the sound of a baby’s urgent wah-wahing. “Before you hurt your baby,” a soothing female voice advised, “Call the number on the screen.”

Then you turn around . . . and you are a grandmother and it’s your child sitting on the couch at 2 am, your child, leaden with fatigue, holding your granddaughter, but watching American Horror Story instead. And you assure her, “Don’t worry. It will pass,” understanding that she doesn’t know whether to believe you or not, knowing that she fears her life just might be over, when in truth it has only just begun.

Comments